While introducing the much-debated electoral bonds scheme the then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley justified the rationale for anonymity. The Supreme Court is presently seized of the petitions challenging the various aspects of the law and the anonymous nature of the scheme. The government has been arguing that the scheme helps to eliminate black money in funding the elections. Petitioners are arguing that masking the identity of the contributors facilitates a nexus between the contributions and the favours that get extended in return, which should ideally be made transparent to the public. It is best to leave the evaluation of the contentions to the court and await the decision. The present article discusses another aspect less in the public view on this subject.

Presently corporate entities can contribute to political parties through the anonymous electoral bonds. Prior to the introduction of this electoral bonds scheme in 2017, corporate donations to political parties had to be reported in the annual report with the details of the recipient of the same. There was also an option, which continues, to route such contributions through an electoral trust.

Electoral trusts by corporates

The electoral trusts were set up by a few corporate groups essentially to cater to their specific set of entities. The contributors to the trust would normally be the group companies. While at the stage of the primary contribution the exact identity of the political party receiving the amount would not be known, the electoral trusts which handed over the donations to the political parties do disclose identity of the party in their books of accounts. These trusts are required to file their accounts and disclose the amount paid to different political parties to the Election Commission. Thus a complete camouflaging of the destination was not possible.

Such trusts were set up by corporate groups like the Tata, Aditya Birla, the Murugappa Group, etc.

Corporate donations

Another aspect relevant to corporate donations was the fact that the Company Law had a limit for political donations at 7.5 per cent of the average profits. With the advent of the electoral bonds in 2017, the said limit was also removed. Hence full anonymity and the removal of the cap happened simultaneously in 2017.

Transparency and disclosure in Corporates

Unlike in the case of an individual or a partnership firm, corporate organisations function through the agency of directors and senior officers. Transparency and disclosure are at the core of corporate reporting for which regulators like the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the department of company affairs, tirelessly strive.

The board of directors of all companies and especially listed companies must ensure that all the affairs of the corporation are meticulously reported to the stakeholders. An independent audit reporting on the same through the verification of the accounts forms the core of corporate governance.

In the case of electoral funding through the bearer bonds, the above premise is entirely torpedoed.

In the case of most promoter managed, but publicly listed companies, the pivotal position of the chairman and/or managing director (MD) would be held by the promoter or a nominee. While the board may have outsiders like the independent directors, sometimes even in a majority, the promoter would hold considerable sway in the formulation and execution of the board’s decisions.

With the legal stamp of anonymity conferred by the electoral bonds scheme, even the board of directors and auditors would get to know only the total funds being contributed and not the details of the political party/parties. The board resolution would empower the MD or the Company Secretary to deal with the purchase and delivery of the bonds.

Questions surrounding the distribution of bonds

Strangely, many corporate directors and auditors take comfort from the fact that the amount sanctioned can only be used to buy the bonds and cannot be diverted to any other purpose. But is this sufficient? Isn’t the decision to divide the contributions to different parties important enough for the board in entirety to be aware of? Even assuming a fair-minded Chairman informally apprises the board of the allocation, how can the actual distribution be checked?

The shareholders, too, would not know the destination of the money and the secrecy strikes at the very root of corporate governance. The situation may be more piquant for a subsidiary of a multinational company if the subsidiary is a material entity for the consolidation of accounts and the holding company’s board seeks details of the contributions made!

Should the court’s decision finally sanctify the anonymous nature of the bonds, the outcome will be in opposition to good corporate governance.

Political parties money anonymously

There is a vital misunderstanding even among lay persons that the political party receiving the contributions do not know the identity of the contributor. While newspapers do not publish the photo of a corporate chief handing over the bonds to a political boss, the mode of transmitting is personal and not in any unseen electronic mode!

That a political party and its head (leader/president) would be unaware of its benefactor is a ridiculous notion. Even more ridiculous is the notion that political donations are actuated by just philanthropical instincts of improving the democratic system!

Under the company law, political donation limit of 7.5 per cent of the average profits was removed in 2017. Based on the data in the public domain, large, listed companies making political donations seldom cross a limit of 1 to 2 per cent of the net profits. (see Table 1 for a sampling of data from a few companies). There is only one company which crosses the 7.5 per cent limit, that too taking just a single year’s profit and not the average of three years.

Rationale behind removing 7.5 per cent cap

However, it is difficult not to feel curious about why the 7.5 per cent cap was removed! And how much would this point weigh with any court in assessing the true intent behind the various limbs of the electoral bond scheme?

In all the above cases, the companies have preferred the route of electoral trust or electoral bonds to avoid disclosure of the names of the political party receiving the donation. It is most likely that even in cases where the contribution was made to the electoral trust, the trust in turn would have acquired the bonds to make the final contribution. Thus, total secrecy would have been ensured in supporting a key democratic process!

In terms of the current structure, a company with three-year’s existence as mandated by the law, with no operations and little capital, can take a bank loan and donate. Only the naïve would ask how a company with no financial strength can obtain a bank loan!

There is an assertion on the part of the administration that a robust KYC and tracking process can help detect fraudulent transactions; but this is not very clear. Whether or not the court is informed of the philosophical speculations of corporate governance related issues, it would be seriously failing in its enquiry if it doesn’t call for the complete records of all the corporate donors which donated large sums to see if the amounts are a reasonable fraction of the profits, or otherwise.

Making donations public

Even in a situation where the court is persuaded to accept that corporates can affect anonymous donations; it can help to mandate that all companies making donations above Rs 1 crore (or another suitable amount) publish a set of details, similar to publicly listed companies publishing financial results at the end of each year.

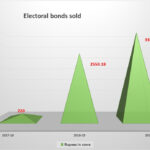

1For the statistically minded, see the graph that shows the electoral bonds sold.

The bonds were open for subscription during various elections for a few days at a time and the figures above aggregate many such tranches in each year.

Mumbai is ahead of all cities

Among the leading cities where bonds were bought in the assigned SBI branch, Mumbai topped with Rs 1880 crore, followed by Kolkata Rs 1440 crore, Delhi Rs 918 crore and Hyderabad Rs 838 crore. Gandhinagar with Rs 211 crore piped cities like Bangalore and Chennai!

Out of the bonds of Rs 6128 crore sold, Rs 6108 crore were redeemed and the portion unredeemed accrued to PM national relief fund!

Face value of bonds

The bonds sold (about 91.76 per cent) were of Rs 1 crore, indicating the high proportion of bulk donations, most likely from the corporates. Bonds are also available with the face value of Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh and Rs 10 lakh and even Rs 1000. Rs 1000 face value may have been included to help migrant labourers to contribute!

How does SBI decide on the number of bond certificates to print in each denomination and who in the bank takes that call? A newspaper report2 citing an RTI enquiry mentioned that between 1 August 2022 and 29 October 2022, SBI printed 10,000 bonds of the face value of Rs 1 crore through the security press, placing the aggregate value at Rs 10,000 crore! Is this a harbinger of the bumper corporate profits in the current year and should the Street take the cue and quickly mount the peak 70,000-points?

The Delhi branch of SBI had redeemed bonds worth Rs 4917 crore (out of Rs 6108 crore) showing that the national capital is the main magnet for this scheme!

Footnotes:

1The statistics may not be accurate as these are culled out from various sources none of which claims to be an authoritative one.